Limits at infinity truly are not so difficult once you've become familiarized with then, but at first, they may seem somewhat obscure. The basic premise of limits at infinity is that many functions approach a specific y-value as their independent variable becomes increasingly large or small. We're going to look at a few different functions as their independent variable approaches infinity, so start a new worksheet called 04-Limits at Infinity, then recreate the following graph.

plot(1/(x-3), x, -100, 100, randomize=False, plot_points=10001) \

.show(xmin=-10, xmax=10, ymin=-10, ymax=10)

Toggle Explanation Toggle Line Numbers

1-2) Plot 1/(x-3) from -100 to 100. The backslash indicates that the command continues on the second line. Not randomizing the points on the graph produces a consistently smoother result, and plot_points=10001 is simply so that SageMath won't draw a line for the vertical asymptote at x=3. Though the graph was plotted from -100 to 100, it is only shown for a domain and range of -10 to 10.

In this graph, it is fairly easy to see that as x becomes increasingly large or increasingly small, the y-value of f(x) becomes very close to zero, though it never truly does equal zero. When a function's curve suggests an invisible line at a certain y-value (such as at y=0 in this graph), it is said to have a horizontal asymptote at that y-value. We can use limits to describe the behavior of the horizontal asymptote in this graph, as:

and

and

Try setting xmin as -100 and xmax as 100, and you will see that f(x) becomes very close to zero indeed when x is very large or very small. Which is what you should expect, since one divided by a large number will naturally produce a small result.

The concept of one-sided limits can be applied to the vertical asymptote in this example, since one can see that as x approaches 3 from the left, the function approaches negative infinity, and that as x approaches 3 from the right, the function approaches positive infinity, or:

and

and

Unfortunately, the behavior of functions as x approaches positive or negative infinity is not always so easy to describe. If ever you run into a case where you can't discern a function's behavior at infinity--whether a graph isn't available or isn't very clear--imagining what sort of values would be produced when ten-thousand or one-hundred thousand is substituted for x will normally give you a good indication of what the function does as x approaches infinity.

Let's analyze a couple of not-so-straightforward examples concerning limits at infinity to ensure a full understanding of how they work. Take a look at this strangely bird-like function:

plot((2*x^4 + x^2 + 2)/(x^4 + 1), x, -4, 4).show(xmin=-3, xmax=3, ymin=-1, ymax=2.5)Toggle Line Numbers

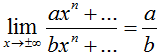

The graph gives it away; the limit of the function as x approaches either positive or negative infinity is two. But what if we didn't have the graph? There are actually a couple of clues as to what value the function approaches at both infinities. Compare the numerator to the denominator: see how the "highest power" of each polynomial is 4? The numerator has 2*x4 and the denominator has simply x4. Perhaps you see where this is going--what do you get when you divide 2*x4 by x4? Why, 2 of course. Simply put, when the numerator and the denominator of a function have the same power--when the highest exponents of x between the top and bottom of the fraction match--the function will have a horizontal asymptote at y equals (coefficient of numerator's highest power) / (coefficient of denominator's highest power).

Well...maybe that wasn't so simple. Let me reiterate with a general case. For a function like this one:

Assuming that n is the highest exponent of both the numerator and denominator and that a and b are coefficients:

For this trick to work, though, the function must be a rational expression (one polynomial divided by another) and cannot have trigonometric or other special functions in the numerator or denominator. For example, the horizontal asymptote of the following function cannot be found using the above method, as it refers to an expression where x is an exponent.

Before you graph this function to see if and where it has a horizontal asymptote, though, let us try a bit of logical analysis. First, which will grow the fastest, e^x or 5^x? Evaluating 'float(e)' in SageMath will tell you that Euler's number e equals approximately 2.7182818284590451, so 5^x will grow more quickly than e^x. But what about the 2*x in the denominator? Consider the growth, now, of 5^x relative to 2*x. When x is 5, the former evaluates to 3125 while the latter evaluates to 10. What you should gather from this is that 5^x trumps all; as x approaches positive or negative infinity, the function will become the quotient of a big number (e^x) divided by a really big number that only continues to grow. In other words, one could write this as:

And tada! There you have it. Comparing relative growths is another way of figuring out the behavior of a function as its independent variable approaches infinity. Continue reading to learn about this lesson's final type of function, those that oscillate.

plot(sin(x), x, -10, 10)Toggle Line Numbers

Like most of the trigonometric functions, as x approaches positive or negative infinity, the sine function itself continues to jump up and down. An oscillating function is one that continues to move between two or more values as its independent variable (x) approaches positive or negative infinity. The limit of an oscillating function f(x) as x approaches positive or negative infinity is undefined. In the plot that you just created, try replacing 'sin' with various other trigonometric functions such as 'cos', 'tan', 'sec', 'csc', 'cot', or any of the arc-functions (like 'arctan') to observe whether they oscillate or whether they have a horizontal asymptote as x approaches positive or negative infinity.

The next graph behaves differently though, as you may observe:

plot(sin(x)/x, x, -100, 100).show(ymin=-1)Toggle Line Numbers

Even though the function oscillates indefinitely due to the sine function in its numerator, I can tell you without a doubt that the limit of the function as x approaches either positive or negative infinity is still zero. But why is this? The sine of a really big number must still be somewhere in the range of -1 and 1, while denominator will simply be a really big number. If we create a table of values, we can watch the function's behavior when x is large. Use the following code to create such a table.

def f(x):

return sin(x) / x

def table():

print('| x | f(x) |')

print('|-------------------|')

for x in [10000..10010]:

print('|%6i | %+f |'%(x, f(x)))

table()

Toggle Explanation Toggle Line Numbers

1-2) Define a function f(x) that is equal to sin(x)/x. The 'def f(x):' signifies

"when f(x) is referenced, do whatever the next indented line says".

4) Define a function called 'table'

5-6) Print the header of the table.

7) Starting at x=10000, perform the following indented command, incrementing x

by 1 every time.

8) Print the current values of x and f(x). '%6i' means "fill six spaces with the

following integer", while '%+f' means "put a positive or negative sign in front

of the following floating point number". The '%(x, f(x))' at the end of the line

tells SageMath which numbers to use when it replaces the preceding percentage signs.

There is another way to prove that the limit of sin(x)/x as x approaches positive or negative infinity is zero. Whether you have heard of it as the pinching theorem, the sandwich theorem or the squeeze theorem, as I will refer to it here, the squeeze theorem says that for three functions g(x), f(x), and h(x),

and

and

,

, .

.

To apply this theorem, we have to find a function g(x) that is less than f(x) as well as a function h(x) that is greater than f(x). Since sin(x) is always somewhere in the range of -1 and 1, we can set g(x) equal to -1/x and h(x) equal to 1/x. We know that the limit of both -1/x and 1/x as x approaches either positive or negative infinity is zero, therefore the limit of sin(x)/x as x approaches either positive or negative infinity is zero. One could write this out as:

and

and

,

, for all x in

for all x in  and

and  ,

, .

.

Toggle answer

Toggle answer

Toggle answer

Toggle answer

Toggle answer

Toggle answer